Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

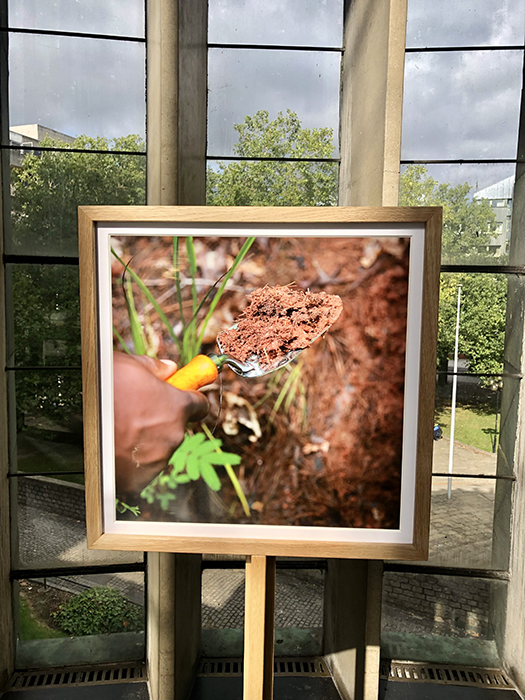

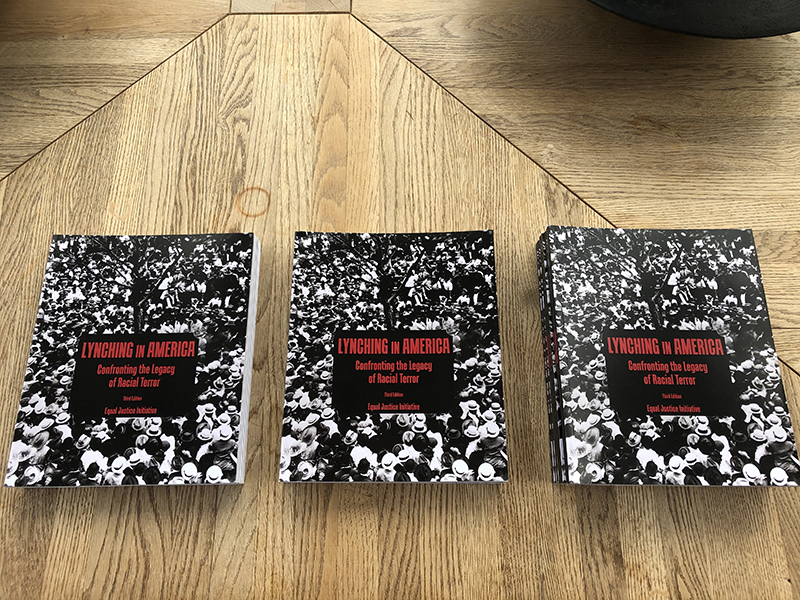

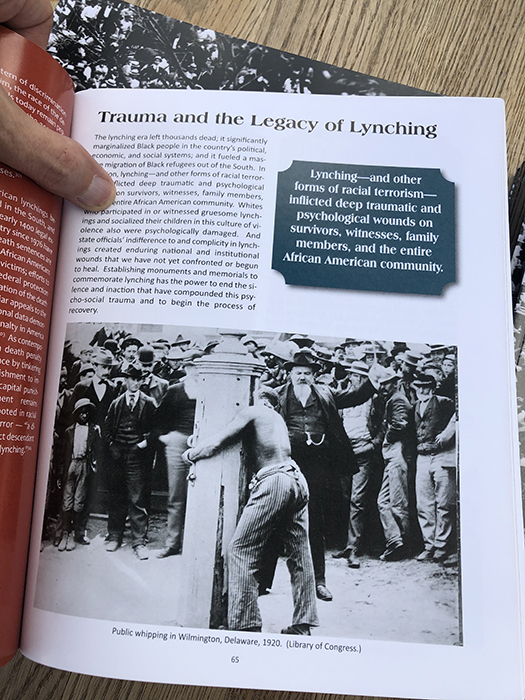

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

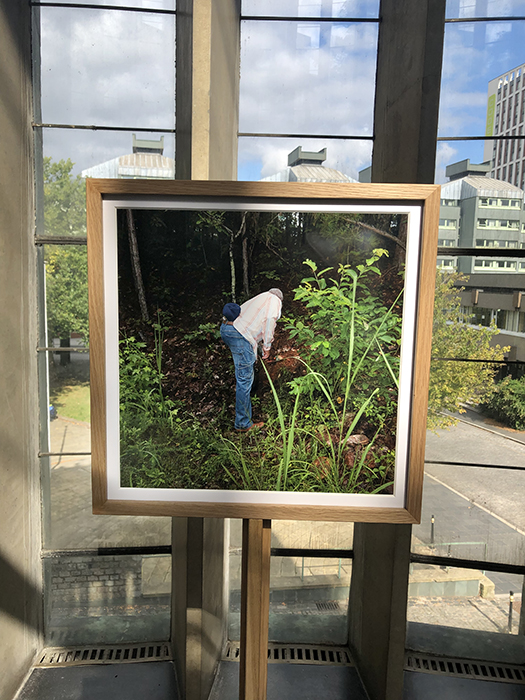

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

Coventry Cathedral 01.10 – 31.10.2021

There can be no reconciliation or healing without remembering the past.

In 1940 as the people of Coventry UK suffered one of the worst bombings of the Second World War a 16-year-old boy called Austin Callaway was murdered in a secluded woodland in LaGrange, Georgia. Throughout Black History Month UK and beyond we come together in empathy and solidarity with the black community inspired by the synchronicity of these two terrible events.

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) began working with communities to commemorate lynching and the traumatic era of racial terror it inspired and its effects on society now by collecting soil from lynching sites across the US. The ‘Community Soil Collection Project’ has provided a tangible way to confront the legacy of racial terror by memorialising the victims and recognising how the whole community has been impacted by such violence. The jars of collected soil across all the known sites in America are now displayed in Montgomery at the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration at the Peace & Justice Memorial Center.

“In this soil, there is the sweat of the enslaved. In the soil there is the blood of victims of racial violence and lynching. There are tears in the soil from all those who laboured under the indignation and humiliation of segregation. But in the soil there is also the opportunity for new life, a chance to grow something hopeful and healing for the future.”

–Bryan Stevenson, EJI Executive Director

“Christ’s suffering as joining with other suffering in the world (and vice versa) is deeply embedded in the Christian tradition. It goes to the heart of the Christian message that God is present in the deepest tragedies bringing love, hope and the possibility of redemption. This resonates deeply with the Cathedral’s and Coventry’s history. Christ’s blood is mingled with the soil and soil is bound up with human belonging.. the idea of the mingling of blood and soil being redemptive is immensely powerful.”

– John Whitcombe, Dean of Coventry Cathedral

In 2017 during a road trip through the southern states, artist and photographer Richard Ansett was invited by the direct descendants of Austin Callaway to join them in the collection of soil from the site of his murder. Ansett has brought back the evidence of this intimate engagement with the family, the community in the hope that it might inspire a similar conversation recognising the legacy of racial injustice the UK.

This personal and allegorical documentation of this simple act makes up an installation that surrounds the alter of the Chapel of Christ Our Servant at Coventry Cathedral as an invitation for empathy and examination of how the past can affect our present. Creating a safe space for the airing of unspoken truths might enable reconciliation and perhaps change.

Artist Statement

The descents’ interaction with the soil represents a form of literal, political and emotional reclamation. “Blood and Soil” appropriated by the far right and chanted by the torch wielding mob in the neighbouring town of Charlottesville (at the same time that these images were created) has been ‘re-appropriated’ in this beautiful woodland as a basic right of all to feel self-assured in connection to our homeland.

The extent of our failure to properly confront the past systematic violent and de-humanising treatment of black people has had an almost epigenetic effect, not only recognised primarily by the inherited PTSD on the black community but as an unspoken legacy of perpetrator and bystander guilt read as inherent in white culture. Left unspoken these are barriers to progress toward reconciliation but they are not immovable if we face these difficult truths together, recognising that our histories are entwined. What otherwise might be read as ambivalence can be re-framed as a withdrawal from events too horrible to face denying the black community the empathy owed and required for reconciliation. These images and their placement in the chapel form a safe space for the beginning of contemplation of these huge questions always prioritising the humiliations and horrors inflicted on our neighbours but also considering the effects these crimes has had on white cultural behaviour now.

Although these images appear on the surface to be a conventional documentary record, I as the photographer am ‘present’ behind the camera. As an invited participant my role is recognised as an equal heir to the legacy of damage affecting us all. As present and conscious participant I reject the detachment of the colonial gaze associated with conventional documentary photographic representation and I further acknowledge my presence as photographer as a reminder of the objectification of victims for entertainment in the production of photo postcards without which ironically there would be no record of these events.

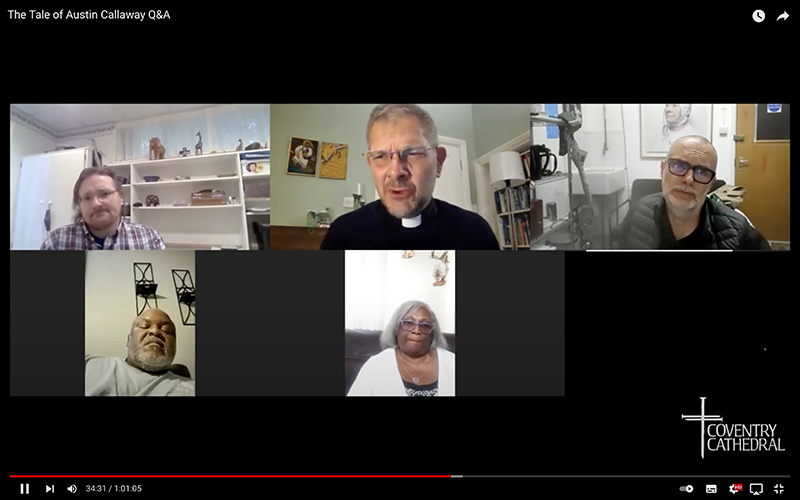

In Conversation with the Dean of Coventry Cathedral and the descendants of Austin Callaway in La Grange, Georgia