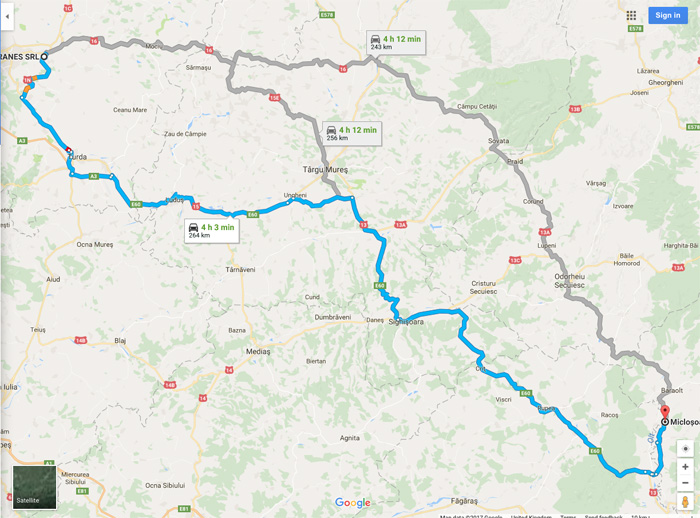

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London and a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.

From Cluj – Napoca Romania to Miclosaora, Transylvania

Arriving in Romania it immediately dispels the myths of Bram Stoker’s Victorian Gothic pot boiler but whilst large stretches on the way to Transylvania have been stripped of any charm by the post revolutionary zeal to develop into a modern state, there are isolated pockets where, what any self-respecting Victorian novelist would still be inspired. traditional ‘peasants’ in comedic national costumes eke out a subsistence living, portrayed in travel photography and tourist guides as ‘the romantic moneyless’ and part of the charm of Transylvania, a low carbon footprint paradise.

Romania’s less attractive alternative realities include its history of pogrom under the Nazis and the Russians, (in Transylvania alone 8000 villages were completely destroyed by the Ceaucescu regime). I arrive with an appalling chest infection propped up by a cocktail of powerful prescription medication that should under no circumstances be mixed with Romania’s notorious plum brandy, Tuica. As I drive through the relative modernity of new motorways and cafe’s called ‘non stops’ I am aware that I am clearly not myself and at a brief stop, I too casually dismiss a gypsy woman begging by the roadside who then whispers something diabolical under her breath in language I don’t understand; a curse feels palpable and personal in my state of mind and in a country steeped in dark myths just 3 hours away from the secular security of London.

Reaching Transylvania I chase the setting sun through small picturesque villages masking deep poverty as hostile dogs sensing fresh blood, chase and bark at the car windows. I arrive at the compound of a real life Count as the light finally gives in to darkness. Not Vlad exactly but a great friend of King Charles, Count Kalnoky and his wife Anna. Kalnoky is as pale as any amour propre Nosfaratu, a cliche of a privileged inbred, socially awkward conservative who has a rather predictable and tedious self-importance that makes one – childishly I admit – want to say “fuck’ a lot. His feebleness engenders a kind of sympathy in me parallel to my loathing. I know it’s not his fault, privilege of this magnitude is disabling and the price paid for a life in a gilded cage. He, unlike his much more interesting wife, avoided the Ceauescu regime being brought up in exile in Munich. Anna however had lived through it and the trauma clings to her – I imagine her as his eyes and ears, more connected to real people but equally unlikeable, she is wildly eccentric with a hard, expressionless gaze that comes from surviving repressive regimes. Anyone, not addled by illness, drugs and alcohol might be intimated. At one point during dinner she stood in the corner, facing into the wall for too long to illustrate the abuse she suffered at school. Speaking to the staff later, they tell me that the locals believe she is a witch.

The heady mix of my medication and the Tuica, a powerful Romanian plum brandy induces paranoid hallucinations, I throw some of it into the huge open fire creating a towering plume of flames and I do my very best impression of an evil laugh. I’m drunk clearly and back in my room I darn’t sleep and only relieved when I can detect hints of the morning light through my curtains.

When I returned to London a large black fly flew out of my ear.